In her speech announcing the recent changes to the Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs (ECCP), Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General Nicole Argentieri gave top billing to a focus on “how companies mitigate the risk of misusing artificial intelligence.” However, getting into the weeds, far more of the changes made to the ECCP (2024 Edits) relate to how companies use straightforward data collection and analytics to monitor, optimize and improve their compliance programs.

In the first article in this multi-part series, the Anti-Corruption Report spoke to experts in the field about the 2024 Edits regarding AI. This second part examines the new questions added that implicate how data is used in a compliance program to identify and mitigate risks, and how data analytics can be used to see how well the compliance program is working, providing value and improving company culture. A future article will discuss additional changes that touch on anti-retaliation, compliance resources and how companies should incorporate lessons learned into their compliance programs.

See “Thoughts From DOJ Experts on Using Data Analytics to Strengthen Compliance Programs” (May 22, 2024).

A Shift in Thinking

While the introduction of the term artificial intelligence was clear and bold, the edits related to data analytics were more understated, reflecting a subtle shift in thinking by the DOJ. The questions added as part of the 2024 Edits are the DOJ’s attempt to assess how a company is measuring the effectiveness of its compliance program through its day-to-day operations.

For example, in the section dealing with the accessibility of policies and procedures, a question has been added asking how the company confirms that “employees know how to access relevant policies.” In the section on risk-based training, a question has been added asking, “What analysis has the company undertaken to determine who should be trained on what subjects?” To determine the effectiveness of a company’s reporting mechanism, a question has been added asking how the company “assesses employees’ willingness to report misconduct.”

All of these questions get at whether a company is taking a rigorous approach to assessing whether each element of its compliance program is risk-based, tailored to the company’s unique risk profile and effective at preventing issues.

Still a Struggle

Understanding what data is available and what to do with it remains a challenge for many companies. “Compliance teams continue to struggle with corporate data,” Angela Crawford, a partner at Crawford & Acharya, told the Anti-Corruption Report. Companies have difficulty understanding what “data” means within their organization, where that data exists, who “owns” the data, and whether there are restrictions or prohibitions to data processing and access. “All these foundational questions must be addressed before compliance teams even can get to the point of accessing, utilizing and analyzing the data,” she said.

See “Lessons From HPE’s Anti-Corruption Purchase-Order Analytics on the Role for Humans in Data Interpretation” (Sep. 29, 2021).

Doubling Down on Data Analytics

Considering that many companies do not fully understand their data landscape, the DOJ’s focus on data in the 2024 Edits may be strategic. “The ECCP is implicitly making the business case for investing in data analytics,” Daniel Wendt, a member of Miller & Chevalier, told the Anti-Corruption Report.

As an example, Wendt noted that the 2024 Edits have added a new section on “Data and Transparency,” which includes the question, “Can the company demonstrate that it is proactively identifying either misconduct or issues with its compliance program at the earliest stage possible?”

“There is no longer the goal of simply detecting and remediating misconduct,” Wendt observed. Rather, companies are now encouraged to use data and transparency to identify misconduct “proactively” and “at the earliest stage possible,” which “presumably reduces all the related harms from the misconduct,” he suggested.

See “How Combining Approaches to Data Analytics Can Yield Powerful Insights” (Mar. 16, 2022).

Access to Data

In the revisions made to the ECCP in 2020 (2020 Edits) a new section was added regarding data resources and access. The 2020 Edits focused on whether the compliance team had access to sources of data and, if there were impediments to access, what the company was doing about them. In the 2024 Edits, the DOJ expanded its focus on access to data with the following detailed questions:

- Do compliance personnel have knowledge of and means to access all relevant data sources in a reasonably timely manner?

- Is the company appropriately leveraging data analytics tools to create efficiencies in compliance operations and measure the effectiveness of components of compliance programs?

- How is the company managing the quality of its data sources?

- How is the company measuring the accuracy, precision or recall of any data analytics models it is using?

Despite access to data being a DOJ expectation for more than four years now, it remains out of reach for many compliance teams. “In my experience, many compliance personnel do not have access to data, or they have access to data but without the resources to do much with it, or they get the data in a less-than-timely way through downloads and extracts at the end of a quarter or year,” Wendt reported.

Sophisticated Businesses Leaving Compliance Behind

Notwithstanding access struggles, companies are ever more reliant on data and analytics for the success of their businesses. “Some organizations are accessing and utilizing consumer and customer data for commercial, marketing, strategic, and financial purposes – but not for compliance purposes,” Crawford observed.

“There is a reasonable expectation that companies – at least in some industries – may be investing significant sums on data analytics for customer engagement or operational efficiencies,” Wendt said. He has seen various examples of companies with robust data science teams, but compliance may have difficulty in acquiring their time and attention.

From the DOJ’s perspective, excuses may not fly. “The DOJ is making clear, once again, that if a company can leverage its data to make money, it also must leverage it to address its compliance and regulatory risks and implement an effective compliance program,” Lila Acharya, a partner at Crawford & Acharya, warned.

See “Transaction Monitoring Tips From the Experts at Google” (May 29, 2019).

Using the ECCP As Leverage

To address problems accessing data, Wendt suggested that compliance teams should make a business plan or proposal to justify any expenses related to increasing access. “Compliance teams are well suited to work with their business partners across functions to message synergies and efficiencies associated with enterprise-wide data analytics,” Acharya said.

But, if compliance teams continue to meet resistance or delays in their access to data, “they can point to this guidance,” Ephraim (Fry) Wernick, a partner at Vinson & Elkins, told the Anti-Corruption Report.

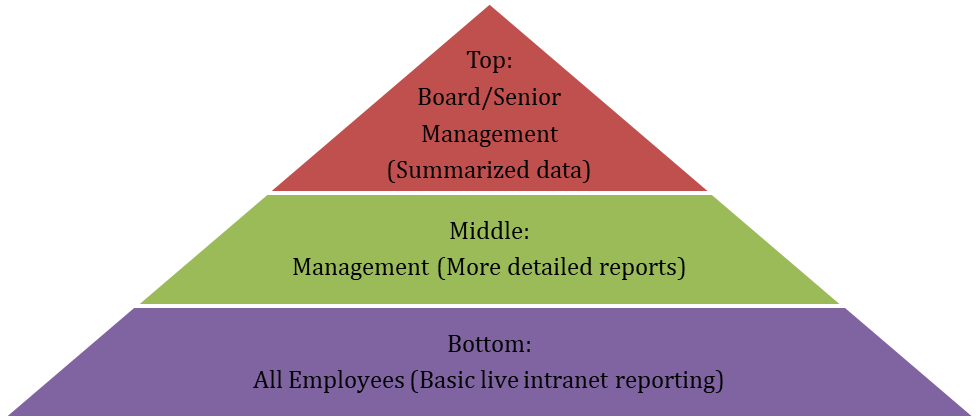

The new language added to the ECCP “is meant to arm compliance personnel to raise a point with management that there should not be huge cliffs in data proficiency across a company, and that a manual compliance program is not optimal in a company that is otherwise embracing the benefits of data analytics and other technologies,” Wendt advised.

See “The Board’s Role in FCPA Compliance” (Mar. 31, 2021).

Holding Up a Mirror to Compliance Programs

While many of the changes related to data analytics get at making the compliance program work better by surfacing risks, the 2024 Edits also encourage companies to use data analytics as a mirror for the compliance program itself. In the “Continuous Improvement, Periodic Testing, and Review” section, two new subsections have been added that touch on this.

The first new subsection, titled “Measurement,” simply asks, “How and how often does the company measure the success and effectiveness of its compliance program?” Additionally, a new subsection on data and transparency has been added that asks:

- To what extent does the company have access to data and information to identify potential misconduct or deficiencies in its compliance program?

- Can the company demonstrate that it is proactively identifying either misconduct or issues with its compliance program at the earliest stage possible?

Commercial Success As a Sign of Strength

In addition to direct measures of success and effectiveness, the 2024 Edits also inquire about measures of the economic value of compliance. Under the section dealing with funding and resources, a question has been added asking whether the company has “a mechanism to measure the commercial value of investments in compliance and risk management[.]”

The added language demonstrates the DOJ’s view that companies with the most effective compliance programs “can show how investments into compliance translate into commercial value or success for the company, either through cost reduction or revenue growth,” according to Wendt.

There are several ways that companies could measure compliance program value. They can attempt to quantify the amount of financial loss prevented by the compliance function, Wernick suggested. A company could also look at instances where due diligence prevented the company from entering into bad business relationships, Wendt added.

The takeaway is that “the DOJ thinks it is important to consider how compliance programs can be additive within a company – not just a cost of doing business – and then marketing those aspects to promote the compliance program,” Wendt said.

See “Using Data Analytics to Boost Compliance Program Effectiveness” (Jun. 27, 2018).

Data to Improve Culture

The 2024 Edits also urge the use of data to assess company culture. In the introduction to Section III – which asks, “Does the Corporation’s Compliance Program Work in Practice?” – a sentence has been added. It states, “Prosecutors should also assess how the company has leveraged its data to gain insights into the effectiveness of its compliance program and otherwise sought to promote an organizational culture that encourages ethical conduct and a commitment to compliance with the law.”

Measuring culture is not easy, but periodic culture assessments and surveys can help. Wernick recommended gathering and analyzing metrics such as “awareness and use of hotlines, belief in the integrity of senior management and fear of retaliation.”

More broadly, “auditing, monitoring and other testing all serve the purpose of comparing whether company actions match company words,” Wendt observed. If there is a mismatch, the actions highlight the hollowness of the words. Data analytics can surface these issues and reinforce “a culture that is in fact committed to compliance with the law.”

See “Compliance 5.0: A Culture-Centered Approach” (Jan. 17, 2024).

Third-Party Due Diligence

DOJ prosecutors also will be probing companies about their use of data analytics in vendor management. In the section dealing with third-party management, the 2024 Edits added the following questions:

- Does the third-party management process function allow for the review of vendors in a timely manner?

- How is the company leveraging available data to evaluate vendor risk during the course of the relationship with the vendor?

Third-party risk management is an obvious place to introduce data analytics because it “remains the highest type of risk” for most companies, Wernick suggested. “Data analytics can be critical in helping to mitigate such risks.”

The data that companies can leverage to evaluate vendor risk varies from company to company. “Financial data can be informative as to vendor risk,” according to Acharya. For example, if a company has a key distributor in a country known for sanctions circumvention, a sudden sales spike is a red flag that should be investigated, she explained.

Companies might also look at hotline and investigations data, as they can provide insight into what countries or regions are subjectively risky for a company outside of objective measures such as the Corruption Perceptions Index, Acharya suggested.

“For vendors, relevant internal data could include payment amounts (any round dollar amounts, for example), mismatches between purchase orders and invoices, changes to company name, address, and/or bank account information, and more,” Wendt observed. “Available data” could also include publicly available information such as information regarding ownership, adverse media and litigation, he said.

No matter what information a company leverages, it should be reviewed regularly, “to inform compliance monitoring efforts, decisions about where to exercise third-party audit rights, and the internal audit team’s annual audit plan,” Acharya advised.

See “Continuous Spend Monitoring for End-to-End Third-Party Risk Management” (Dec. 11, 2019).

M&A

The 2024 Edits have introduced several new questions that relate to how companies integrate and upgrade their compliance programs after a merger or acquisition.

The subsection on post-transaction compliance programs has been almost entirely rewritten, changing from a single high-level question about what the company’s process has been in the past to a more detailed interrogation. The updated section asks:

- What is the company’s process for implementing and/or integrating a compliance program post-transaction?

- Does the company have a process in place to ensure appropriate compliance oversight of the new business?

- How is the new business incorporated into the company’s risk assessment activities?

- How are compliance policies and procedures organized?

- Are post-acquisition audits conducted at newly acquired entities?

Additionally, edits were made to the subsection dealing with integration, asking about the integration of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems as well as the role that compliance and risk management functions play “in designing and executing the integration strategy[.]”

Integrating ERPs

The 2024 Edits get highly specific about ERP systems like SAP, asking, “Does the company account for migrating or combining critical enterprise resource planning systems as part of the integration process?”

The inclusion of this specific question continues the 2024 Edits’ focus on using data and data analytics to mitigate risk. ERP systems can include many different types of software that help run a business, but the DOJ is likely most interested in those that are used for budgeting, accounting and other financial management, Wendt suggested. If a newly acquired company uses a different ERP to conduct activities than the parent company, the parent company “is going to have a lot less visibility into specific transactions,” he said, which “increases the risk that someone may be able to successfully hide high-risk transactions or even improper payments.” Additionally, using multiple ERP systems may make any efforts toward data analytics costly or even impossible. “The DOJ may be emphasizing the importance of ERP decisions because it is so important for setting the stage for effective data analytics efforts,” Wendt concluded.

The M&A Safe Harbor

In October 2023, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco announced a new program that provides leniency for companies that identify and remediate compliance issues after a merger or acquisition (M&A Safe Harbor).

Both additions to the ECCP regarding M&A “aligned with the M&A Safe Harbor policy expectations,” Amy Schuh, a partner at Morgan Lewis, told the Anti-Corruption Report. The role of compliance and risk management in the integration strategy “is critical to the company’s ability to integrate internal controls timely, which is an expectation of the Safe Harbor policy,” she said. The added question regarding who will oversee compliance at the new business “simply boils down to accountability,” she noted, which is also “critical to obtaining the benefit of that Safe Harbor.”

“In my mind, DOJ’s M&A Safe Harbor program is the most significant of the numerous policy proposals this Administration has put in place as it has the potential to truly incentivize self-reporting in the aftermath of a M&A deal,” Wernick observed. The 2024 Edits that touch on M&A are “a natural follow-through” from the Safe Harbor, he said, and will help to create an environment where compliance issues at a newly acquired entity can be identified and self-reported quickly.

However, the 2024 Edits do not incorporate all of the elements of the M&A Safe Harbor, which is interesting, Wendt said. One of the most controversial pieces about the M&A Safe Harbor is the tight timeline it requires for companies to avoid liability. “[T]o qualify for the Safe Harbor, companies must disclose misconduct discovered at the acquired entity within six months from the date of closing,” Monaco noted when announcing the program. The 2024 Edits make no mention of the appropriate timeline for integration. “Similarly, while there is general language about ensuring ‘compliance oversight,’ there is no specific language about encouraging the new employees to raise allegations of misconduct and/or for reviews of all existing allegations post-closing (when the buyer has full access to all information).”

See “Safe Harbor Policy Seeks to Encourage Self-Reporting of Issues in M&A Transactions” (Oct. 11, 2023).